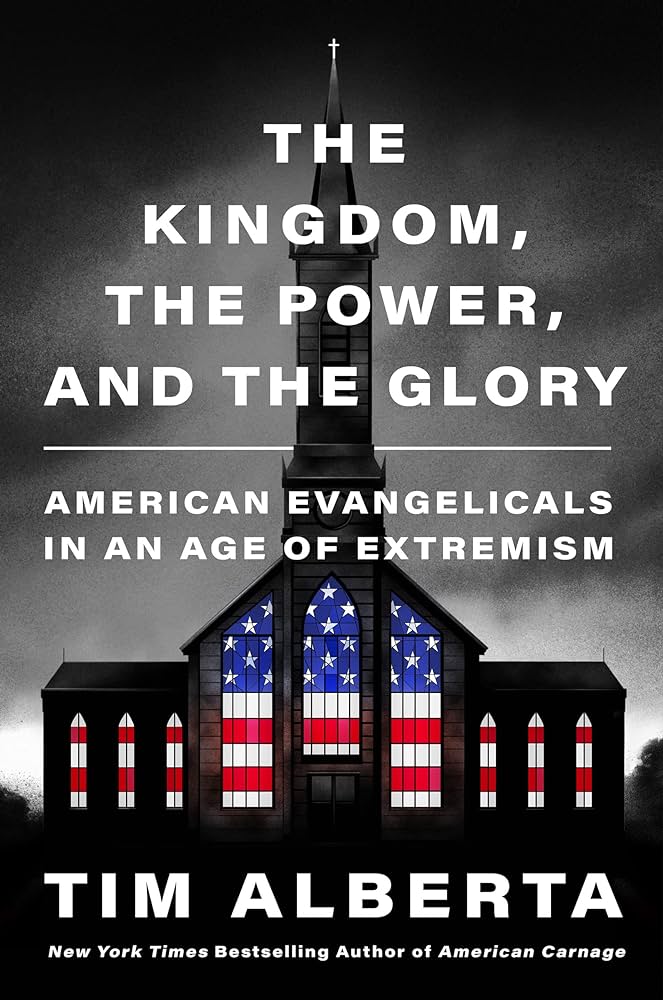

Tim Alberta is a Christian evangelical and an accomplished journalist describing what he sees as a growing division inside America’s evangelical churches. He visits and describes events within congregations of numerous mega-churches across the country. A vocal minority (he describes them as a minority, but I’m not sure anyone is counting) of right-wing nationalists have transferred their faith from Jesus Christ to Donald Trump. They are led by like-minded Republicans and by pastors praying for their presidential protector of beleaguered and oppressed Christians in America.

Alberta does not challenge evangelism’s core conservative principles: opposition to abortion, anti-LGBQTIA+ sentiments, Christianity’s promise of a heavenly Kingdom to come, and the necessity of bringing the word of Christ to unbelievers. But he is unstinting in his questioning of how personal conservative beliefs have become militant rallying cries that, in his words, violate the spirit of Christ.

Yet he wonders, how have Christ’s teachings to love your enemies, to welcome the stranger, and to care for the downtrodden turned into a winner-take-all political battle? Why have evangelicals been among the country’s leaders in turning away immigrants, trolling public health advocates promoting Covid vaccines, and on the front lines of the January 6th uprising?

The book suggests that the problem is misguided spirituality and he does his best to quote scripture back at those he perceives to be fanatics. But he also describes a movement that is constructed to absorb what it is told on faith. So when congregants get all of their information from charismatic preachers and an endless supply of right-wing, and deeply conspiratorial news sources — Covid was created by cabals to control churches; elections are fixed by “woke” Democrats and the Deep State — there is not much congregational initiative to question.

Alberta points an enraged finger at the Falwells, the Moral Majority, Liberty University, The Southern Baptist Convention, scores of preachers who have sexually abused their congregants, and hucksters who raised millions of dollars preaching hatred to evangelicals terrified that they are losing their God-anointed Christian country.

Near the end of his book, he does his best to point to a resurgence of what he considers sane-minded evangelical Christians. He predicts a forthcoming split of nationalistic churches from those who are Jesus-centered. A schism is the most optimistic outcome he can point to.