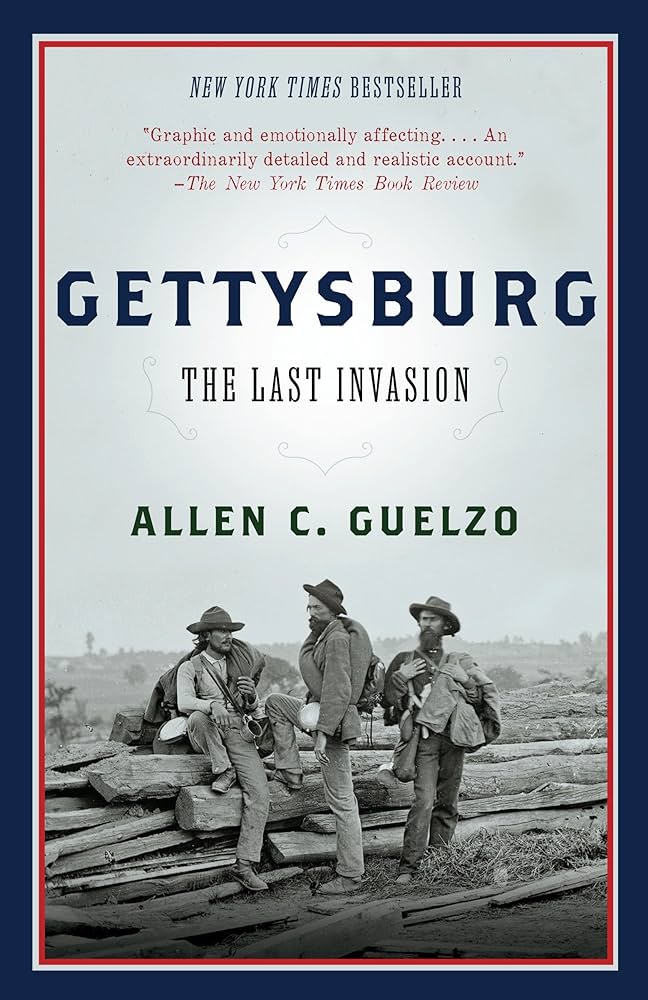

Tens of thousands of books have been written about the Civil War, and thousands have covered one of the most significant battles of the conflict: the invasion of Gettysburg by General Lee and his confederate rebels and its defense by the Army of the Potomac. I read this book in preparation for an insider’s tour of the battlefield I was given by Dr. Carol Reardon.

Guelzo’s take is to zoom in on the experience of less well-known officers beneath the famous Generals Lee and Meade and then to zoom in further to the experience of individual soldiers.

General Lee’s objective was to invade the north and by so doing create enough carnage and dissent among anti-war Northeners that he could draw them to the negotiating table. Lee’s counterpart, General McClellan of the Army of the Potomac, was widely popular among soldiers and politicians, but on a field of battle so cautious that he avoided every opportunity to fight. Just three days before the face-to-face meeting at a crossroads in Pennsylvania, following McClellan’s dismissal, George Meade was appointed General of the American army.

The three days of battle in the heat of July turned on a hundred small calculations, luck, ineptitude, and fortunate timing. The outcome was so closely contested that a single successful artillery barrage or an attack begun five minutes earlier or later could have altered the outcome.

On the battlefield, Guelzo makes us feel the challenge of moving roughly a hundred thousand men on each side across scores of miles of countryside to take up position. Then he explains what a soldier had to endure, marching day and night without rest, proper nutrition, or kit before being dumped directly into battle. Guelzo also explains that guns were far from accurate and that compensation for an inability to aim accurately or see an enemy through a dense fog of gunsmoke was to fire a hailstorm of bullets. Trees were stripped of leaves and branches. Artillery blasted away. Men were torn to shreds in an age before the discovery of germs or antiseptics; horses were broken and discarded like so many tanks.

Reading between the lines, the political adeptness of Lincoln is exceptional in holding together his coalition. The primary goal of the northern states was to preserve the union, not necessarily abolish slavery. Furthermore, many Americans in the north objected far more to Lincoln’s policies of warfare, were opposed to the Emancipation Proclamation, and were more interested in continuing their economic partnerships with southern producers (read slave owners) than in paying taxes to fund a war.

Unfortunately, Guelzo clearly does not like General Meade and fails to give him credit for expertly deploying his forces to fend off General Lee’s attack.

Above, the field across which Pickett led the famous last charge of the rebellious south at Gettysburg.