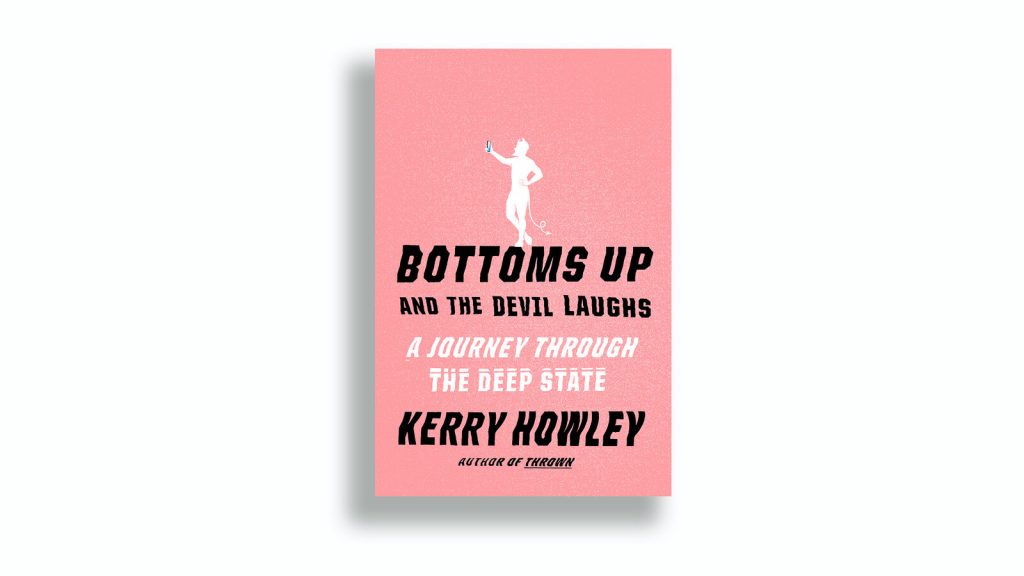

Kerry Howley digs deep into the lives of American whistleblowers: John Walker Lindh, Chelsea Manning, Reality Winner, and Edward Snowden. Each was charged with violating national security laws and faced the full force of an American law enforcement system designed to shut down all security risks. Howley argues that the laws were established hastily while the dust was still smoldering at the World Trade Center. The laws have enabled waterboarding, torture, secret detention camps, Guantanamo, solitary confinement, psychological torment, and imprisonment without representation or trial. They also permit America’s spy agencies to track our phone calls. Agreements we’ve made with Facebook and Google, for example, mean we have traded away a good deal of our privacy. Online collectors gather our interests and our visitations in order to promote the next advertisement to appear in our feed: someone is making a profit by monetizing us.

On one side of the argument the world is a dangerous place. Non-state actors and secretive emissaries of hostile governments are working around the clock to destabilize America. Only constant and unrelenting vigilance can protect us. On the other side, argues Howley, at least some of the Americans she highlights were neither malicious nor dangerous. Their treatment by the American government is very far from upholding America’s values.