The book’s subtitle is accurate: A Personal History of Modern Ireland. This history of Ireland begins in 1958, more or less, when O’Toole was born. In the 1950s, Ireland was an Old World agrarian country: nearly three-fourths of the population worked farms. Families were enormous, schooling was negligible, the government corrupt, and the Catholic church set values, standards, mores, and rules. Economic gain was achieved, as it had been for centuries, by emigration.

This is the story of how in just fifty years Ireland not only joined the world of modern, high-tech, gig-economy nations, but also passed some of the most anti-Catholic, pro-Abortion, pro-LGBTQ+ laws in the world. It is hard to think of another country in the world that has undergone such a transformation in so short a period while maintaining relative stability. Or done so without a revolution.

O’Toole’s thesis is that there were, and always have been, two Irelands. On the one hand the structure of church monitored, inviolate rules on marriage, divorce, sex, sexuality, and devotion. Yet, on the other, the church itself violated nearly every one of its own rules by disappearing children born out of wedlock or into inescapable poverty into severely abusive private institutions. They beat children in regular schools. They incarcerated mothers with unwanted pregnancies. They sexually assaulted children for decades.

Concurrently, Irish people swore allegiance to the Church, while living authentic lives reflecting the full gamut of human desires: they were sexually active, they loved people of the same sex, they sent their daughters to England for abortions, and they invented work arounds for birth control.

The country changed in the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s as government corruption and clerical abuses became too large to ignore. In essence the private lives of Irish people became public at the same time that the private abuses of church and state were finally acknowledged.

The lessons for me is the ability to be hypocritical or to hide the truth from our eyes while it stands in plain sight is not a uniquely Irish trait. We Americans also maintain principles based upon mythology: we are supposed to be a country of equal opportunity where hard work and strong family values are all one needs to get ahead. And yet the lived experience of many Americans is riven by uncrossable class divides and deeply entrenched racism, all plainly visible if we choose to look.

The good news is that if Ireland can make a leap into the first world of commerce and culture in just two generations — and hang onto much of its core culture — is it possible that other countries in Africa or Asia might do the same?

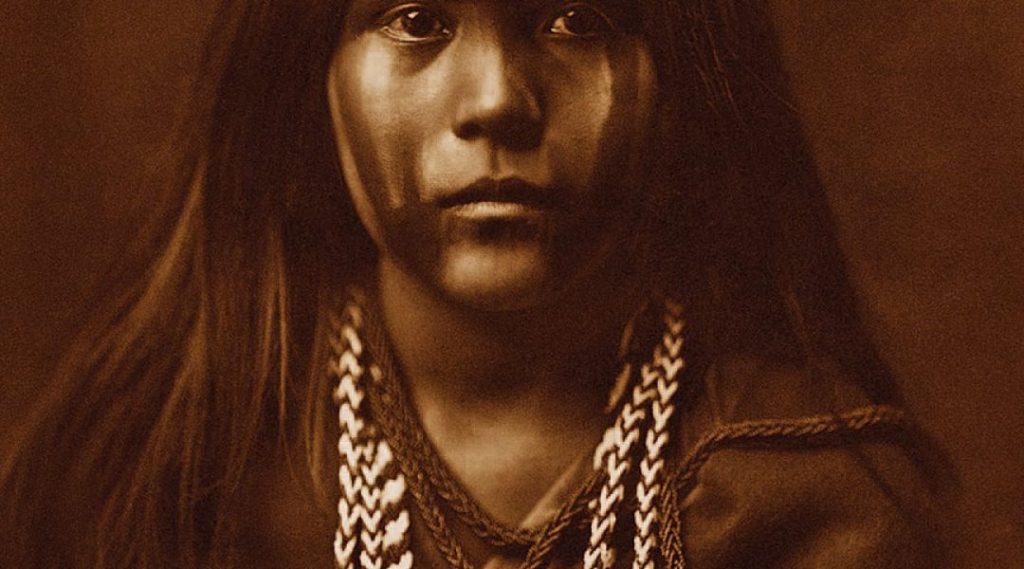

At the end of the nineteenth century, because no one had ever been there, the virtual consensus among geographers was that the North Pole resided in a warm, open sea. One needed only to sail a ship through the ice surrounding it to reach the open ocean. In 1879, Captain George DeLong and a crew of 30-plus sailors set off for the North Pole. At end of the their first year, their ship, having failed to find open water, was instead frozen in place, where they remained out of communication with the rest of the world for three years. Half of their time was in near total darkness and nearly all of their days and nights were below freezing. Finally, sheets of ice crushed and sank the U.S.S. Jeannette. The crew walked and sailed for hundreds of days across ice floes and freezing oceans with hopes of reaching the coldest landmass on earth, the north coast of Siberia. The test of human physical and psychological endurance is simultaneously contemporary and otherworldly. The relationship of European and American men to the environment, native people of the Arctic, to women, and stoicism is history not to be overlooked.

At the end of the nineteenth century, because no one had ever been there, the virtual consensus among geographers was that the North Pole resided in a warm, open sea. One needed only to sail a ship through the ice surrounding it to reach the open ocean. In 1879, Captain George DeLong and a crew of 30-plus sailors set off for the North Pole. At end of the their first year, their ship, having failed to find open water, was instead frozen in place, where they remained out of communication with the rest of the world for three years. Half of their time was in near total darkness and nearly all of their days and nights were below freezing. Finally, sheets of ice crushed and sank the U.S.S. Jeannette. The crew walked and sailed for hundreds of days across ice floes and freezing oceans with hopes of reaching the coldest landmass on earth, the north coast of Siberia. The test of human physical and psychological endurance is simultaneously contemporary and otherworldly. The relationship of European and American men to the environment, native people of the Arctic, to women, and stoicism is history not to be overlooked.