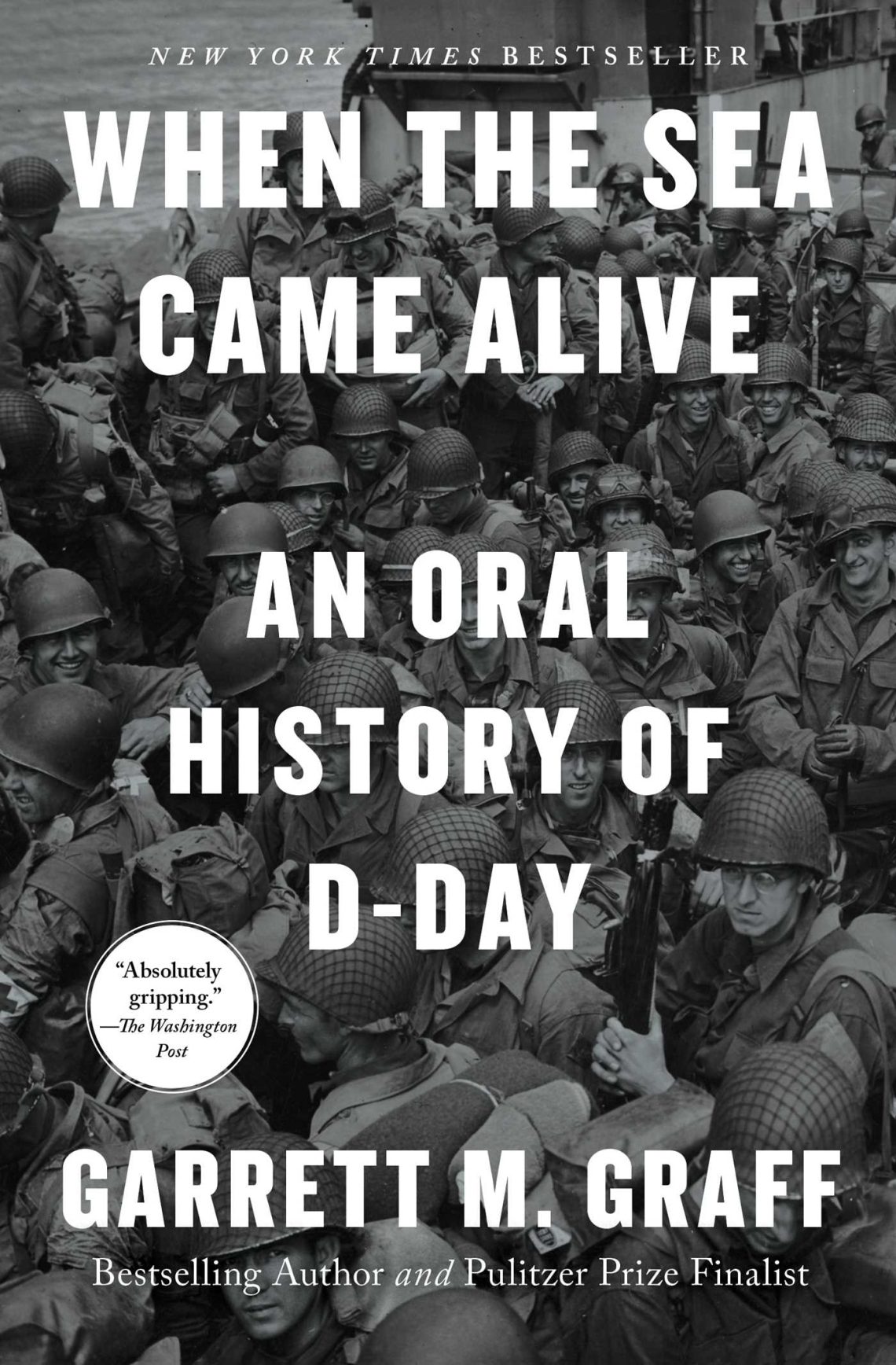

Graff brings to life one day in a very long war. On June 6th, 1944, Allied Forces landed on the beaches of Normandy, France and began to push back Germans from their fortified Atlantic Wall. Graff’s account is delivered entirely with quotations. The recollections of participants give the invasion intense immediacy.

Among the unsung heroes are the planners of the invasion. The level of detail required to put 150,000 troops ashore borne by 7000 vessels across 60 miles of coastline is staggering. Having only incomplete information regarding the enemies strength and positioning, they began planning a secret attack a year in advance. The militaries of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and other nations had to account for tides, moonlight, weather, sea state, number of daylight hours, and all of the possible German responses to a continental invasion they fully expected. Every ship had to have sufficient fuel to cross the English Channel as many times as it was expected to, as did every offloaded Jeep and tank have to have enough fuel to carry it as far inland as commanders needed. Then additional fuel needed to be transported and soldiers had to be trained and assigned to run, while under fire to fill up the fuel tanks of the appropriate moving vehicles. Soldiers in the right numbers and the right places had to be ready for men killed or wounded.

Troops needed food, clean socks, soap and enough medical attendants to cope with a number of casualties that could only be estimated. All 7,000 ships had to have their routes planned so their cargoes were discharged without conflict with neighboring ships and in water shallow enough so neither soldiers nor materiel drowned.

The miracle of D-Day is that the planners got it right.