It is no small feat to write a history of the United States. Choose any event, say, for example the Presidency of George Washington, The Civil War, the long, and ongoing struggle for Civil Rights in America and you will discover that on just a single subject there are hundreds, if not thousands, of books on the subject. What Jill Lepore does so expertly in this book is summarize key events, lots and lots of them, and place them in a political continuum that is America’s history.

Lepore says at the outset that her focus is politics and beginning in 1492 when Christian Europeans planted flags on the American continent in the name of Christian conquest for Europe. At nearly the same time America became a far away home for Europeans, and then others, some of them enslaved, seeking freedom from religious and state orthodoxies. America started as a country of contradictions. A country of immigrants, wherein a very significant portion of the population today is anti-immigrant.

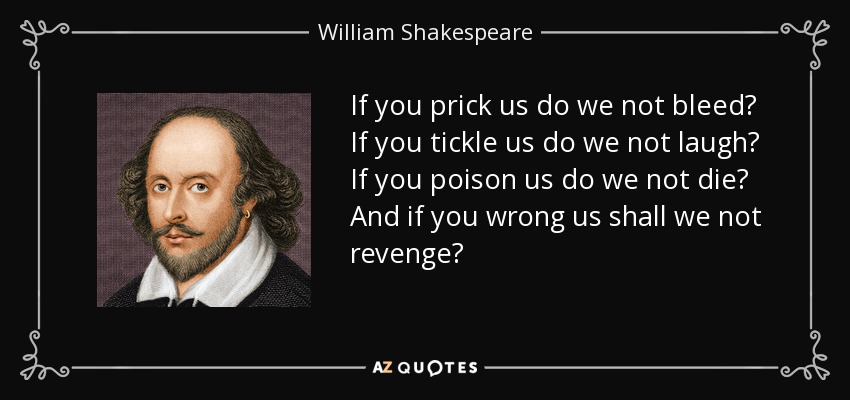

From the first days when Thomas Jefferson wrote, “We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal…” Lepore makes clear that internal inconsistencies and conflicts were going to be papered over with daub and wattle. At the time of the writing of the Constitution, a first of its kind, the notion that citizens were not inferior to noblemen was truly revolutionary. Yet, “all men” failed to include enslaved men, or women.

The title of the book is so multilayered as to become an unbreakable wire threading the entire book together. Especially interesting are the final fifty years of American politics (perhaps because I have lived them and can observe how Lepore selects and summarizes the events she highlights) when the notion of truth has become so personal that the question of whether we can hold together as a nation that believes in something unifying feels like it might be hanging in the balance. The expansion of the Internet and with it Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, 4chan, and Truth Social (Trump’s personal twitter), has allowed both the insertion of genuine Fake News (see the work of Russian troll farms during the 2016 election) and the selection of personal, unedited news selected by each and every consumer to suit her or his preconceived beliefs. The book was published before the January 6 uprising and attack on Congress, which is the predictable outcome.

These Truths is not an optimistic book, and the work of right wingers to promote hundreds of years of inequality, racism, sexism, anti-foreigner sentiment, misinformation, and objection to facts is wholly dispiriting (I suspect the right dismisses Lepore’s book precisely because it raises uncomfortable truths). The new Left’s closed-door approach to speakers and writers whose views they find dangerous to insecure minorities or their definition of an illegitimate history is scarcely more encouraging. Still, there is nothing like observing a master putting history into a clear and readily accessible context.