Just as every year is now the hottest on record, so too the number and intensity of wildfires across the planet break annual records for temperature, acreage burned, and never-before-seen fire behavior. A warming climate, low atmospheric humidity, pre-dried forests, and human habitations in previously uninhabited ecosystems are all tinder waiting for an inevitable spark.

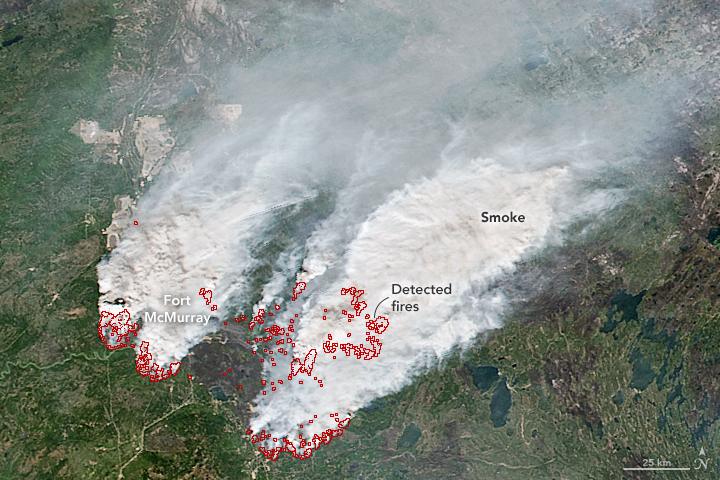

What makes this book so insightful is its focus on fires in 2016 that demolished the city of Fort McMurry in Alberta, Canada. Fort McMurry is the home to Canada’s bitumen deposits of tar sands, the worlds least efficient and, after coal, most carbon intensive fuel. In essence, the oil extraction industry warmed the planet enough that it set itself afire.

Further, human habitations, now interspersed in forested and tree-lined communities everywhere, are constructed with fuel for fires. House fires can be contained if a single home goes up, but are uncontrollable when a wall of intense heat flows toward a neighborhood. Homes are fabricated with kiln-dried wood and filled with wooden furniture and cabinetry. The number of household items made of oil-based synthetic products is surprising: vinyl siding, carpets, sofas, pillows, clothing, electronics. To a raging fire, it is all just fuel. Then add the propane tank for the outdoor grill, the gas tank for the SUV, and cans of sprays and paints in the basement and homes tend to explode before a fire even reaches them.

Interspersed with the minute by minute account of the explosive growth of the Fort McMurry fire is a detailed, and unequivocal litany of warning about human induced climate change caused by the burning of fossil fuels. The evidence and scientific proof has been around for more than 100 years, albeit in some marginal locations. Still, by the 1950s and definitely by the 1980s, there was widespread agreement that burning fossil fuels would cause the climate to change. I was explaining this in lectures already in 1987.

What kind of evil is embodied in corporations and individuals whose internal memos acknowledge the repercussions continued fossil fuel extraction would have on the livability of our planet? Favoring profit or people, Vaillant leaves no doubt that they paid obfuscators to confuse the public and protect their profits.

This book, a National Book Award finalist, should be required reading, but it should also be read only on the first floor. At the end when the reader jumps out the window she can live to recommend the book to someone else.