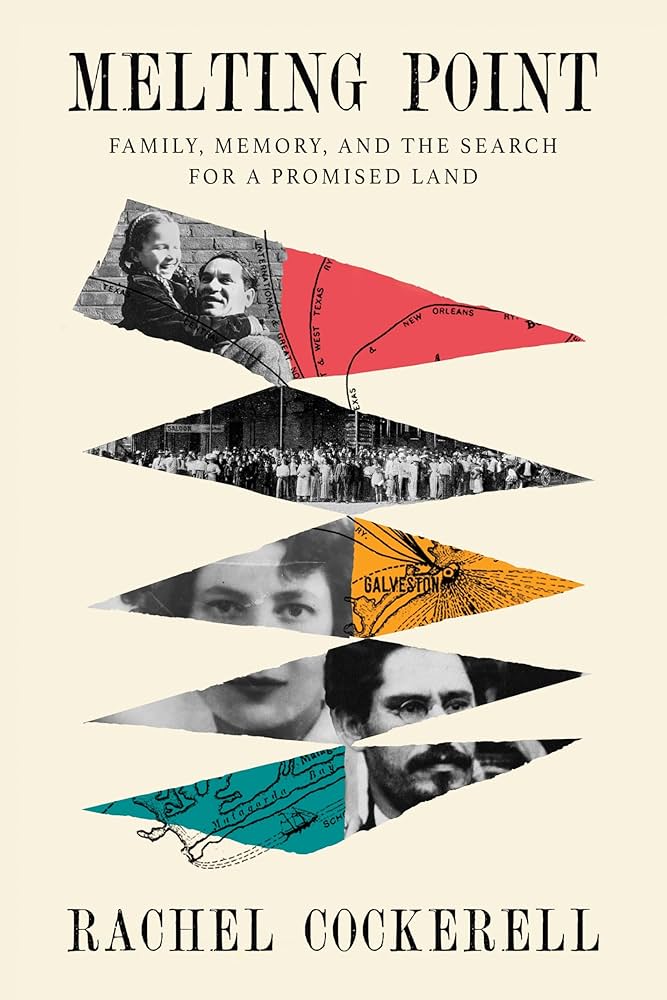

Really three distinct books in one cover. Each book covers the biographies of relatives of the author. The first, and longest of the three, describes the early calls for Zionism, with special attention to the highly influential, and all-but-forgotten British author: Israel Zangwill. Israel Zangwill was best friends with Cockerell’s great grandfather, David Jochelman, also an influential zionist. When the first Zionist congress was called in 1897 representatives came from across Europe, Russia, the Middle East, and North Africa. They all carried the same story of generations of pogroms. The need for a safe Jewish homeland was underway as it was clear that nowhere in the world was safe for Jews.

Some victims of the Kishinev Pogrom.

By 1903, the vicious pogrom of Kishinev, Russia, intensified the fear of Jews around the world. Even the U.S. was not a safe haven. The tenements of the lower East Side were overcrowded and disease ridden. From the perspective of Europe, America, too, had reached its point of saturation.

Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side of Manahattan.

The author covers in great detail the debate over whether to take a British offer of land in Uganda or wait for an opening in Palestine. The audacity of British colonialists to offer land because no one of consequence inhabited any of Great Britain’s colonies is appalling. The question of whether to take Uganda or wait rent Zionists into two camps: proponents of Palestine whenever it might come and practicalists searching for any safe harbor. Rachel Cockerell’s relatives were in favor of bringing Jews to safety immediately. They helped transport thousands of Jewish refugees to Galveston, Texas.

Making Melting Point exceptionally interesting is that it is written entirely in first person accounts. Cockerell deftly and expertly weaves together a story using only quotes from other people. Book one, by itself, deserves **** (of 4).

Book two covers Cockerell’s relatives in New York in the 1920s and book three her relatives in London before and after WW II. Aside from being related to the author, it isn’t quite clear why these people are important.