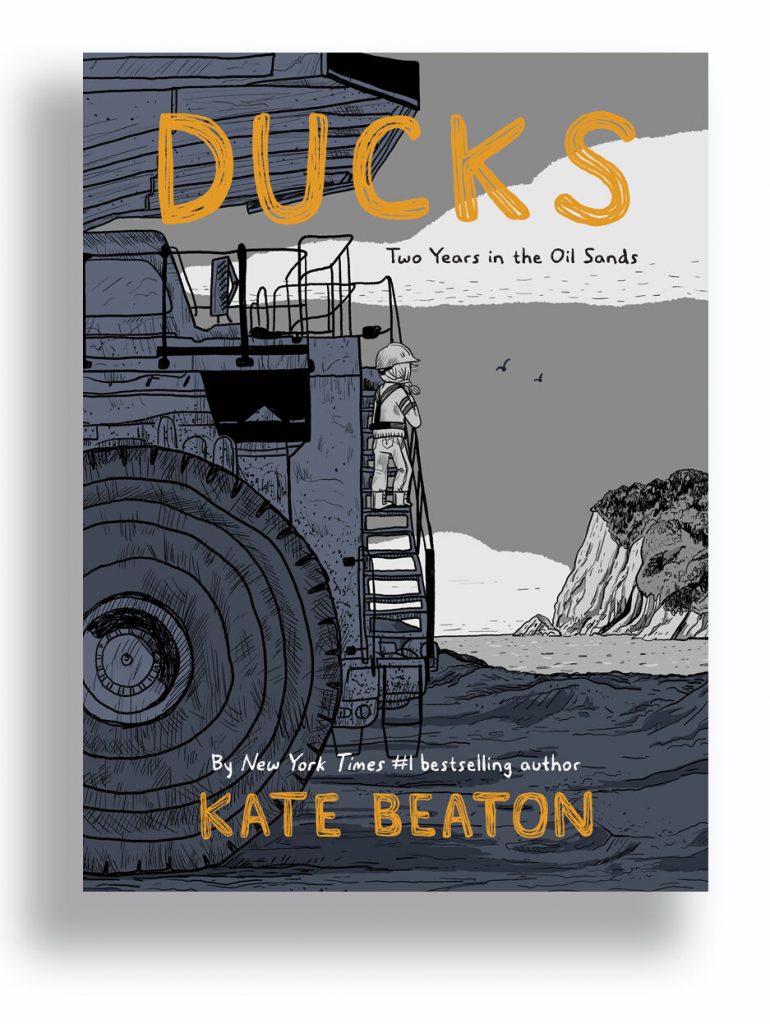

Newly graduated from college with artistic talent, a liberal arts degree, and a mountain of college loans, 21-year-old Kate Beaton departs her economically depressed home in the Canadian maritimes in search of work and income to pay down her debts. Like many other Canadians, she emigrates to the land of big salaries, the oil sands of Alberta.

Ducks is a coming of age story endured by many college graduates who combine wanderlust, a can-do attitude, and the immortality of being young. Not unsurprisingly she faces isolation, loneliness, and the exhaustion of trying to adapt while working as hard as she can in a new land far from home.

But Kate is also immersed in a sea of roughnecked men in a frozen, dark wasteland bearing little semblance to a balanced society. The level of sexual aggressiveness and mistreatment directed at the few female employees is appallingly high and carefully rendered in cartoon characterizations, generally six panels per page for more than 400 pages. While the book’s title might refer to a band of migratory ducks poisoned in a waste-tailings pond, it probably also refers to the author’s position as a “sitting duck” hunted by predatory miners far from their own families, hope, or the restrictions of normal civilization.

Separating men from women, implies the author, in mining camps, college dormitories, the army, or by religious restriction is likely to lead to sexual degradation of women, LGBTQ+, and anyone with perceived or conceived weakness.