Lea Ypi is now a distinguished professor of political theory at the London School of Economics. She wanted to describe for readers what life in her native Albania, the last “purely” communist country aside from North Korea, was like prior to its conversion to a more democratic society. Ypi (pronounced Ooopie) begins each chapter with a vignette from her childhood and finishes each with an analysis of political forces at stake. We learn the rules of queuing for rationed commodities; the artistic and status value of owning a smuggled coke can; how the tensions of career paths assigned by the state, rather than chosen, wore down her parents’ marriage; and how something called an unalterable “biography” was deterministic for navigating society.

It is not clear why each story has to be seen through the eyes of young girl, but I think Ypi is doing more than personalizing her experience for readers. She is writing more than a memoir. What she is saying, is that when the State decides what you can do for a living, what you can purchase in a store, or where you can live it infantilizes all of its citizens.

For much of the book, Ypi overlooks heinous actions of Albania’s secret police. That overshadowing is made up for by her critique of capitalism. Albanians were not paralyzed by too much choice, never had to face the difficulty of desiring more than they needed, so no one, she claims, ever really felt poor. Health care and education were available to all. In fact, societal divisions caused by class, sex, or race were theoretically abolished by the communist state. By comparison the inequality meted out by the dog-eat-dog competitiveness of capitalism feels hopelessly unjust. The rich get richer and the poor seem never to break free.

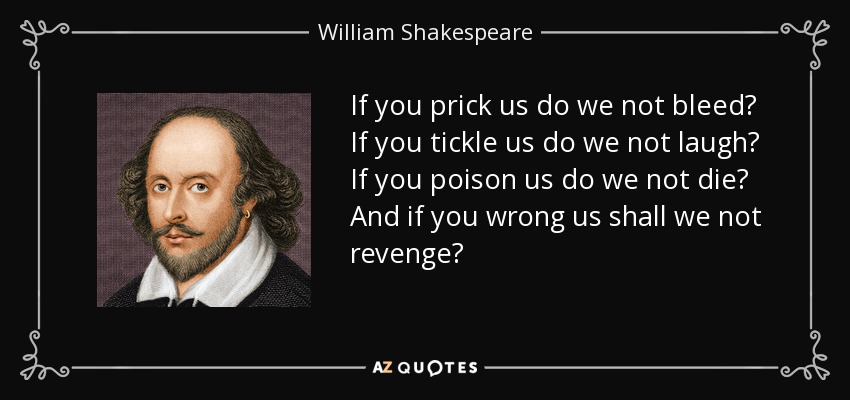

In the end, Ypi’s comparison of Marxism and capitalism criticizes both systems. Under Marxism, man dominates his fellow man. Under capitalism, it’s the other way around.