How did we not know this?

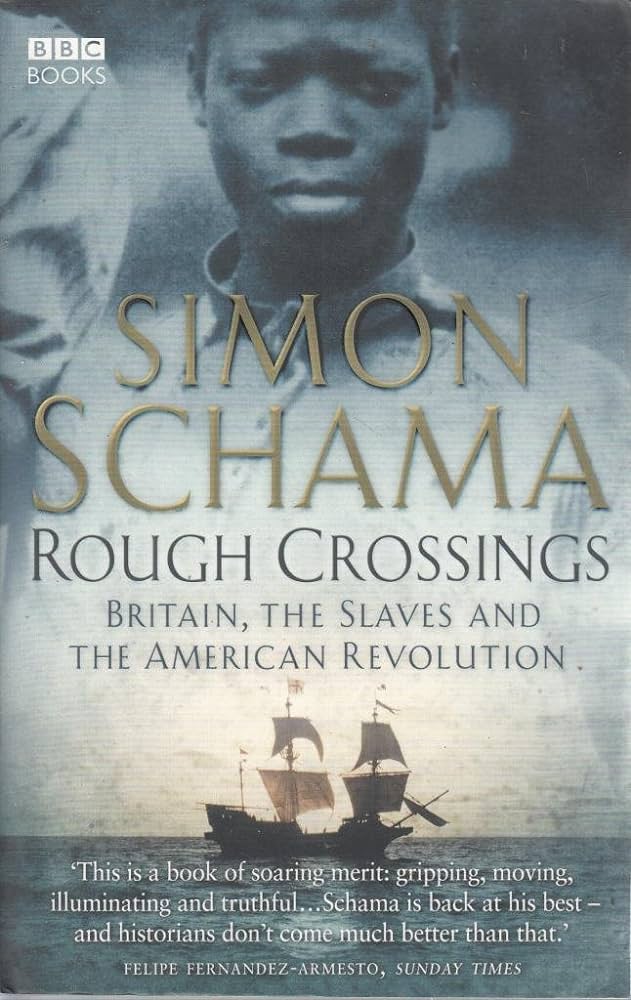

In the 1760s, a court case in England suggested that any person of African descent living in Great Britain was a free man. Enslaved Africans in America knew about the court ruling. Moreover, they were well aware that Jefferson’s paragraph in the Declaration of Independence had been deleted. Jefferson, though a slave-owner himself, recognized that the hypocrisy of a declaration calling for freedom, equality, and the removal of the tyranny by unjust overseers could not be squared with the maintenance of American slavery. The Declaration of Independence would not be ratified by southern states so long as Jefferson’s paragraph endured and the issue of slavery was postponed until a later date.

Nonetheless, enslaved Blacks reasoned that the enemy of my enemy is my friend. By the thousands, African Americans fled to British lines, and many Blacks fought against Americans. Perhaps as many as one-fourth of all enslaved Africans escaped plantations, only to find they had backed the losing side.

After the war, as southerners sought to reclaim their lost “property,” Blacks did their utmost to make their way to Great Britain. Three thousand Blacks, for example, were in New York City at war’s end, under the protection of British troops.

Thousands of Blacks moved to Nova Scotia, because it was part of Great Britain. (Check out the link, Our History-Black Migration in Nova Scotia.) They were promised land, but promises were broken. In 1792, 1,192 men, women, and children sailed out of Nova Scotia for Sierra Leone to start a free Black nation on the African shores from which many families had begun their journey. In one poignant early election in Sierra Leone, community representatives were voted on by men and women of the newfound village. Which means the first women in history to ever vote were formerly enslaved Africans.